Aging is a universal challenge, with people from all walks of life facing many of the same challenges as their bodies get older. Yet, different societies vary in how they approach aging.

There are also many changes over time, as demographics and values change. Many countries are finding that younger generations are more interested in traveling and are less likely to settle down, raise large families, and care for their aging parents.

The differences between generations and between countries offer fascinating insights into the things that drive us as people and as caregivers. Some of these differences can help to give you insights about your own caregiving journey and help you work out the best approaches for you.

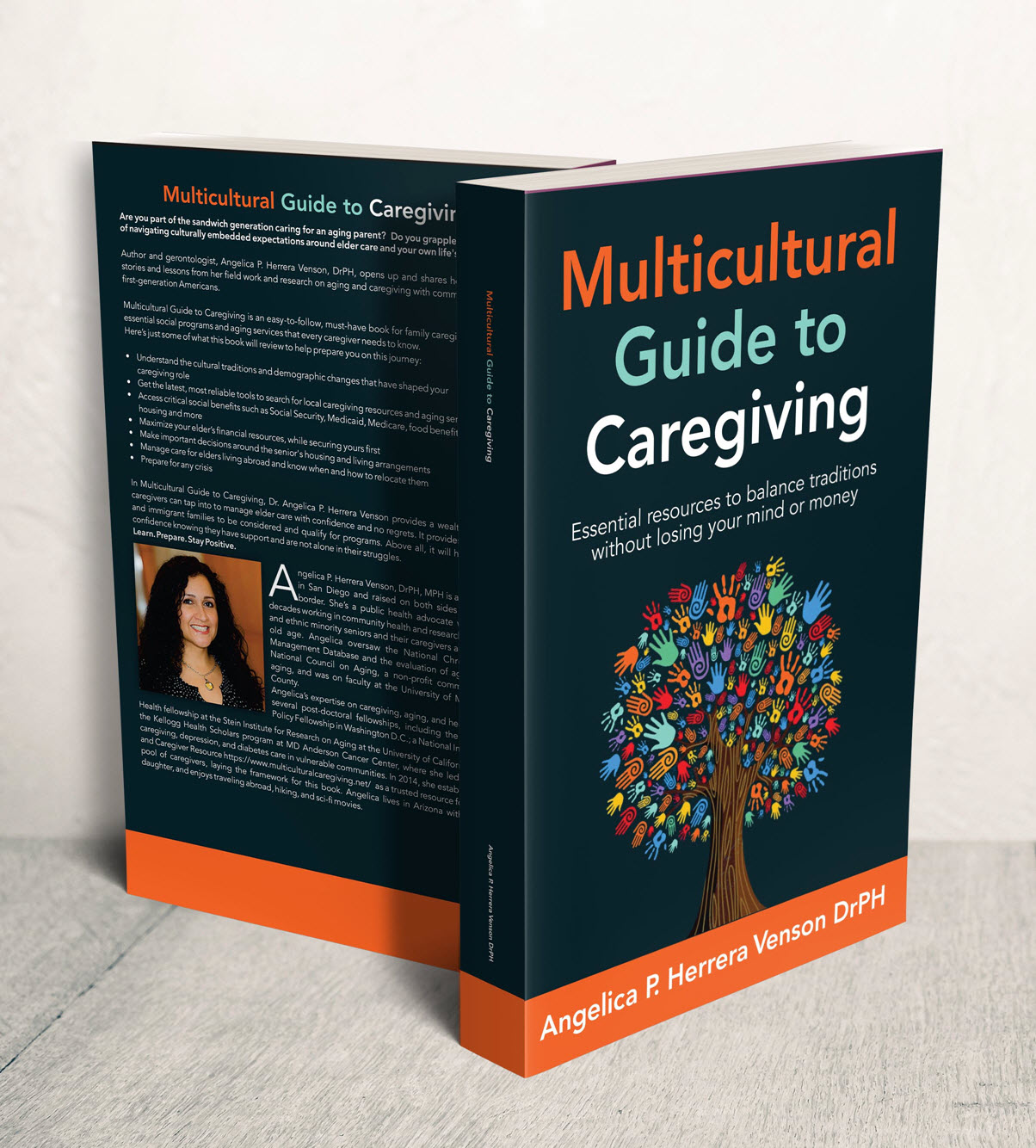

If you reside in the U.S., check out our new book, Multicultural Guide to Caregiving. Our goal is to help families with roots in countries outside of the U.S. to better tackle caring for aging parents, even from a distance. We connect you to critical benefits and social services in the U.S., as well as strategies for managing the financial demands of elder care across the seas.

You can also check out our other posts on caregivers in different cultures, including Hispanic caregivers, Vietnamese Americans, and Ethiopians.

Caregiving in China

For 2500 years the Confucian doctrine of Xiao, or an intergenerational responsibility to one’s elders, has required adult children to care for their elderly parents. Most families had several children, meaning that there were multiple persons to care for the elderly.

Thus, the only people requiring institutional care in their sunset years were those without adult children.

Caring for the elderly in modern China has changed dramatically since the rise of the Communist Party. One factor in particular, the One Child Policy, in which each family unit is limited to bearing one child, has made it extremely difficult for the single adult child to care for their parents.

The burden on only children is proving unsustainable, with China’s previously unburdened elderly support institutions suddenly overwhelmed with people who do not possess the family support that Chinese society’s structure demanded.

These, among other factors, are ushering in a modern age of new hardships for Chinese families caring for the elderly.

Institutional Care is Costly

Despite China’s incredible economic growth, most Chinese families are still poor compared to Westerners.

As the need for institutionalized care has expanded with the reduction in average Chinese family size, professional care has become more difficult and expensive to acquire.

This means that even when modern Chinese family values do align with the importance of caregiving, the families often lack the resources to do so successfully.

Confucianism, Reversed

In contrast to previous perceptions of institutional elderly care, modern Chinese family values view elderly homes as superior 24/7 care facilities.

In fact institutionalizing an elderly family member has become a luxury which humble Chinese families are proud to provide their relatives, but never boast of. The prominence of institutional care has flipped so completely that now home care is considered a secondary, undesirable choice for families.

Old Confucian ideals of respect, loyalty, and material provision for the elderly were so deeply engrained in Chinese culture and law that there was little need for institutions at all. Now, however, with fewer children to care for the elderly, institutions are booming.

Modern Transportation Creating Distance Between Families

Another factor changing Chinese elderly care is the greater geographic mobility of Chinese families.

Prior to modern transportation, it was common for the same family to stay in a single area for many generations. Now it is quite easy to fly or drive to a new location for school, more scenic location, less polluted city, or better job opportunities.

China is even developing a vast matrix of bullet trains, the fastest in the world, but this is not enough. Some studies claim that more than half of those in elder home care have children who live too far away to care for them.

This has resulted in a change to modern Chinese family values where it is no longer uncommon for families to live quite some distance from one another and from elderly relatives.

Fewer Children Means Fewer Caregivers

As stated earlier, China’s One Child Policy has created a number of difficulties for Chinese families, forced sterilization, abortions, and gender ratio distortion included. It has also made it more difficult for a couple to care for both sets of aging parents.

If there are no other siblings to share the responsibility, the financial and emotional burden will be substantial.

Strain on nuclear families can lead to higher rates of divorce, dysfunctional family units, and children with higher rates of emotional and social disorders.

A Woman’s Job

Women used to be expected to assume a greater portion of the care required for aging relatives. This is changing as well, however.

Women are attending school at higher rates, meaning that average Chinese women are more empowered and thus less likely to be pressured into being the sole caregiver of their parents.

Elderly Care is Booming in Response to Demand

In the 80’s and 90’s institutional care was stigmatized – a last resort for those elders who had no money, no children and no relatives.

Now however, China’s service industry is becoming much more entrepreneurial and relies less on funding from central government sources.

Moreover, Chinese families are becoming more affluent and increasingly able to pay high fees to keep their relatives in private residential care. The elderly care business is booming, but still falls short of serving China’s massive population.

Shortage of Residential Care Beds

China’s government is acutely aware of the need for more residential care beds and currently there are provisions for only 1.6% of the elderly population. The World Bank standard for developed nations is 8%. Government action is required to make up the difference.

Long-Distance Caregiving

Given the nature of a rapidly urbanizing economy, Chinese families are increasingly geographically distant from one’s parents, which means that providing care is no longer always feasible.

The problem is becoming more acute as less and less of the population resides in rural locations, and families are increasingly split between cities.

Limited Regulations for Quality Elder Care

As in other areas of the economy, there is a lack of serious regulation governing the institutional care of the elderly in China. Presently the government employs a system whereby families are reimbursed for in-home care, rather than institutional.

Policy changes are required to increase the entrepreneurial investment required to provide care for all those who need it. Some advocates are also calling for a government-instituted accreditation process allowing families to judge the quality of care at any particular institution.

Lack of Qualified Caregivers

Attracting foreign investors and care operators is another challenge. Gaining a license to operate a private care facility in China is difficult and staffing the facility once the license is granted can also prove challenging.

Because elder care is not a well-established profession in China, there is currently a lack of qualified geriatric caregivers. Government subsidies for education and training programs in this field would alleviate some of the crisis.

The Multicultural Guide to Caregiving

Multicultural Guide to Caregiving is an essential resource for balancing cultural expectations around elder care, without losing your mind or money in the process.

Feeling Overwhelmed?

Check out our Caregiving Consulting service for personalized support and guidance.

Leave a Reply