Most content on this blog focuses on the ‘average’ caregiver. Such caregivers tend to be women, often aged between 35 and 65, and spend 20 hours a week or more providing care. Some of these women are juggling the twin burdens of providing care for aging parents and their own children. Some are even attempting to hold down jobs at the same time.

However, today, we want to look at caregiving outside that traditional group.

It’s time to consider the caregivers who aren’t talked about as often. Doing so is crucial, as we don’t all face the same challenges. Differences between us can also vary the types of support we need.

So, let’s take a look at the different groups and how to help with the specific challenges they face.

Spousal Caregivers

Caring for a spouse (or other romantic partner) includes the typical physical and emotional challenges of caregiving, along with an extra layer.

Many caregivers in this situation struggle with the changes that are occurring in their romantic relationship. This is particularly true when one partner has dementia, but there are plenty of challenges for other health conditions as well.

The Complexities Of Caring For A Spouse

The Loss Of Support

Couples develop a close bond, where they are often relying on each other for practical and emotional support. Losing that is tough, especially when the spouse’s illness or injury comes on suddenly.

This issue can be even more devastating for very insular couples or those with a relationship that has lasted decades.

What happens if your spouse is your main source of support and the person who you solve problems with, then they cannot be that anymore? Suddenly you’re not just in a difficult situation, but you’re there without one of your main sources of support.

This is rough, as it takes time to establish close friendships with other people. Even if caregivers do find good close connections, they’re not likely to be as strong as the one between husband and wife.

Grief Over a Lost or Changed Relationship

There’s often a grief aspect to caring for a partner, even when they’re not dying.

That grief is often partly for the relationship and where things could have gone next. It’s grief for the loss of what could have been.

Say, for example, a couple is in their late 20s and the man gets in an accident and is paralyzed from the waist down. That accident would forever change some things for the couple. Some dreams might die entirely. Others might become much more difficult.

This issue is particularly significant for health issues that dramatically change a person’s ability to function or even to connect with their partner. Here, it may feel like a huge aspect of the relationship has been lost.

It’s not surprising that there’s a grief and adjustment process.

Their Challenges Often Aren’t Well-Recognized

When a severe illness, like dementia or cancer, strikes a family, the focus is often on the person who is sick.

In family situations, the next area of focus is on the children. How are they coping with their mother or father’s illness? How can they best be supported?

It’s easy to overlook just how much the other parent is being impacted.

This parent might feel guilty for some of what they’re struggling with too. For example, in Neither Married Nor Single, Dr. David Kirkpatrick talks about some of the emotions, complexities, and decisions associated with his wife’s dementia. Some of these are areas not often discussed, including changes to the romantic and sexual relationship.

Kimberly Williams-Paisley also touches on the topic in Where the Light Gets In, although she does so with much less detail.

What Spousal Caregivers Need

Most of all, spousal caregivers need support – particularly support that’s outside their regular circle of family and friends.

This is crucial, as spousal caregivers need to work through and come to grips with the complex emotions they’re facing, including grief and possibly resentment or anger. Doing this with family can be tricky, as there’s the risk of one person’s emotions and struggles triggering those of another.

Therapy and support groups for spousal caregivers are particularly valuable options. Even the right online forum can be a good place to explore some of the emotions.

Spousal caregivers may also need to examine what to do about currently unmet needs. For example, some husbands/wives of late stage dementia patients choose to take a lover or have a fully fledged secondary relationship to ensure their sexual and relational needs are met.

In some other situations, the spouse who needs caregiving may give their blessing for the caregiver to have an extramarital sexual relationship.

Such approaches aren’t the right fit for many couples, but for the right people and situations, they can be incredibly helpful. They’re also just one example of why caregivers should think outside the box. You need to find the right answers for you. Those might be very different than the answers for someone else.

Millennial Caregivers

Millennials are becoming a bigger and bigger part of the caregiving population. This is the group that’s often caring for children and parents (or grandparents), while still trying to work.

Specific Challenges

Millennials also face some major challenges, partly because their financial situation is often worse than caregivers from previous generations. This can increase stress and may make some aspects of caregiving harder.

Some caregivers in this situation may not have a home of their own and may be renting instead. This adds another layer of challenge to the situation, leading to extra stress and insecurity.

Because these caregivers are relatively young (between 26 and 41), they have a lot of life left ahead of them. This creates some difficult situations:

- Younger caregivers can easily end up in extended caregiving roles, particularly if their parents are only in their 50s or 60s. This could easily lead to caregiving for 10+ years.

- Long caregiving roles can lead to increased long-term negative impacts, including health impacts, disruption to careers, financial difficulties, and relationship disruption.

- Some caregivers, particularly young ones, end up going from one caregiving role to another, such as caring for an aging father, then mother, then a father-in-law. This can be draining and lead to many years where the caregiver doesn’t get to live their own life.

Hidden Strengths of Millennial Caregivers

Millennials tend to be a flexible generation. Many are good at adapting to challenges and finding creative solutions to problems. We’ve only got better at doing so since the COVID lockdowns.

Millennials are often good with technology as well, which helps them to use the internet to find solutions and social connections. This was certainly the case for me. It was difficult to leave the house when I was caregiving, so online friendships were my main source of engagement with others.

Some millennials are also able to leverage their skills and backgrounds to make money more creatively. This includes making money online or tapping into the gig economy.

Also, because millennial caregivers tend to be younger, they’re often healthier than other groups of caregivers. After all, anyone providing care in their 60s or 70s is going to have their own health problems to contend with.

Younger Caregivers

Some caregivers are younger again, perhaps just 20 or 25. Such caregivers might be supporting a grandparent (or even a great grandparent), rather than a parent.

Younger caregivers have many of the same issues and strengths as millennials. This includes being more flexible and healthier, but less financially secure.

An additional issue is that this age is where people start to establish their lives, particularly in terms of relationships and careers. If your 20s and early 30s are severely disrupted because of caregiving, there can be flow on effects for the rest of your life.

Because of this, it’s crucial that young caregivers find as many ways as possible to still engage with their careers and find whatever opportunities they can. Doing so will often include creating a support network and sharing the caregiving load.

Doing so isn’t selfish at all. It’s realistic and reasonable.

Having a group of people provide care and support is often better anyway, as this reduces the risk that anyone will burn out.

Neurodivergent Caregivers

Neurodivergent is a broad term that refers to people whose mental or neurological function is different from normal. It’s most often applied to autism spectrum disorder, although that’s far from the only example.

The term neurodivergent is partly a recognition that the differences in neurological function don’t need to be negative. Many even come with benefits.

However, we live in a society that’s somewhat ableist and people who are different often do not fit in well.

This means that neurodivergent individuals sometimes need to find alternative approaches to some aspects of life.

What Does This Mean For Caregiving?

The impact of neurodivergence on caregiving really depends on the type of neurodivergence you deal with and how it presents.

For example, a caregiver with ADHD might struggle with routines and focusing during visits with the patient’s doctor. A person with dyslexia, on the other hand, could find it difficult to read and understand medical information.

People’s experiences vary dramatically, so there’s no one-size-fits-all approach to caregiving as a neurodivergent. Instead, it’s best to experiment and see what works for you.

There are some very good forums and Facebook groups that can help people find the accommodations that work best for them. For example, I’ve seen conversations about different ways of organizing information and how to deal with the issue of ‘out of sight, out of mind’ for organizing.

The most important thing is recognizing that it’s okay to do things differently than the norm. Look for the approaches that work for you, regardless of anyone else.

Minority Caregivers

Being part of a cultural minority group can also present challenges, particularly for caregivers whose first language isn’t English. It can be much harder to access appropriate support. Many people in this situation don’t even know where to look.

There are also differences in cultural traditions and expectations to deal with. For example, some minority seniors may be very uncomfortable with the Western medical model and may be unwilling to accept some types of treatment or medication.

Other times, caregivers may find that medical staff are not willing to be culturally sensitive.

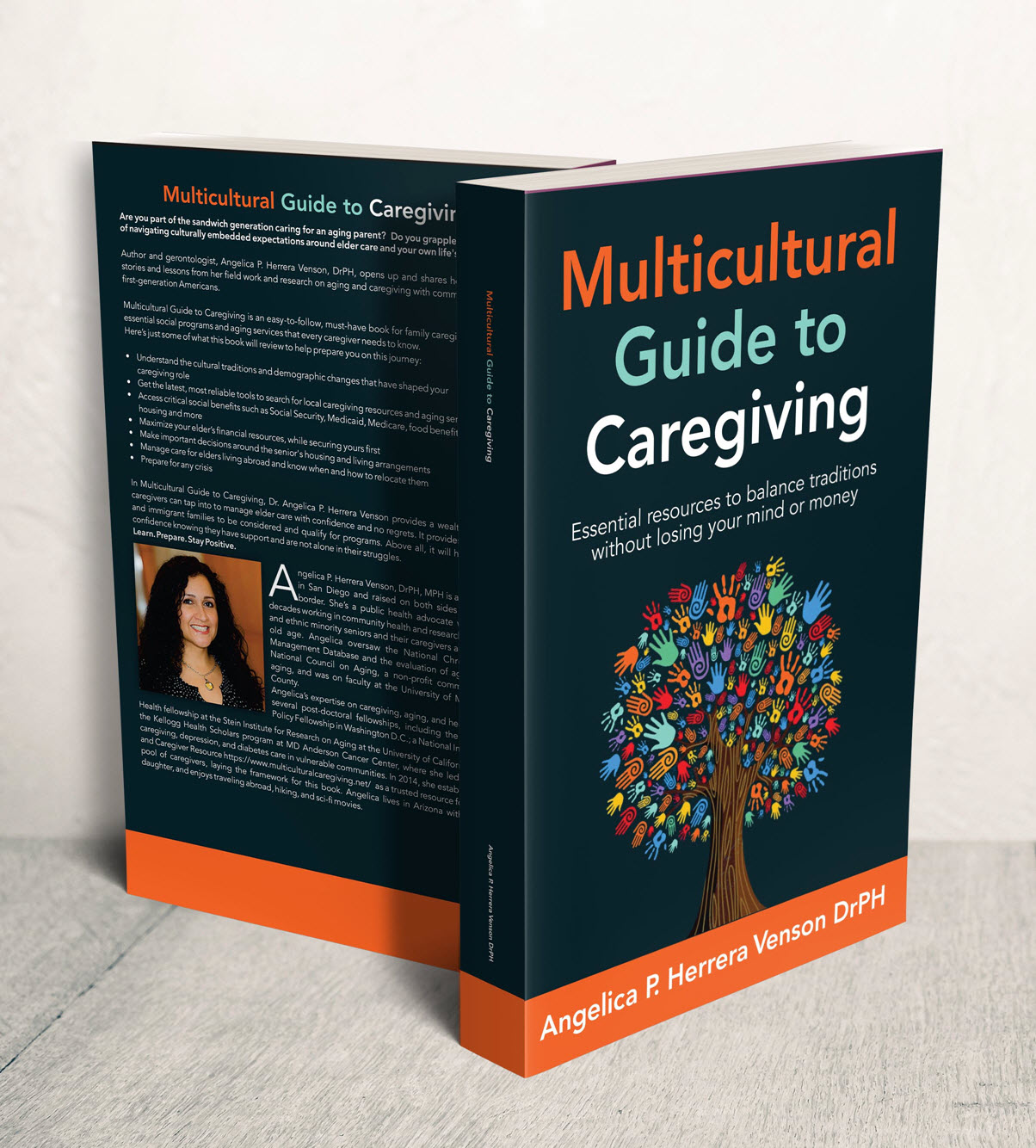

These challenges and more were addressed in depth in The Multicultural Guide to Caregiving. This book, by Angelica Herrera Venson, examines the specific challenges faced by minority caregivers in the United States, along with how these difficulties can be navigated.

Senior Caregivers

Advances in healthcare mean that people are living longer and staying more functional into later life (they’re even saying that 70 is the new 50).

This increase in longevity creates challenges though, as seniors still need support, particularly towards the end of life.

Much of this support comes from family members, particularly adult children. So, an aging senior of 85 or 90 might have their son or daughter as a caregiver – who is perhaps 65.

The problem is easy to see.

Many people will have some health issues at 65, ones that are just likely to get worse with the strain of caregiving. In some cases, the adult child might even die before their parent, partly because they aren’t taking care of themselves as well as they need to.

How To Support Senior Caregivers

Aging caregivers are a particularly vulnerable group, especially as they can face considerable health challenges of their own.

The truth is that many caregivers in this situation can’t safely care for an aging parent or spouse on their own. They need support – often a considerable amount of it.

It may even be necessary to step away from caregiving entirely and find alternative arrangements. Doing so can be incredibly difficult and guilt-inducing, yet may actually be better for both seniors in the long run. After all, caregivers who hit burnout often aren’t effective at providing care and may even put their loved one at risk.

Male Caregivers

Male caregivers aren’t as rare as you might expect. Some estimates even suggest that around 40% of caregivers are male.

Men face many of the familiar challenges of caregiving, but also tend to have smaller support networks and are less likely to seek support, even when they’re overwhelmed. Smaller support networks can increase the risk of caregiver burnout and could contribute to mental health issues in male caregivers.

This is an area that urgently needs attention. It suggests the need for male-specific programs and support networks. Such approaches would help the

Final Thoughts

What does all this mean?

For one thing, it highlights the need for flexibility. There’s no one size fits all approach, as caregivers and their situations are too different from each other. Even caregivers within a single group, like millennials, will be in vastly different situations and have their own distinct needs.

To do well, caregivers often need to take a trial and error approach. This can involve looking at different potential approaches, then experimenting to see what works and what doesn’t. Don’t feel locked into a particular approach simply because it is expected or ‘normal’. The best approach for you might be completely different.

The Multicultural Guide to Caregiving

Multicultural Guide to Caregiving is an essential resource for balancing cultural expectations around elder care, without losing your mind or money in the process.

Feeling Overwhelmed?

Check out our Caregiving Consulting service for personalized support and guidance.

Leave a Reply